The problem with data brokers: targeted ads and your privacy

news Paul Jarvis · May 10, 2022We’ve all had unsettling moments where we believed our computer was spying on us, listening to what we said out loud, or seemed to remember better than our own memories, what we had clicked on days or weeks ago by showing us ads for similar or related items.

There are countless stories online of people searching for a specific product once, then being bombarded with ads for similar products forever after.

But targeted ads for products you may not want to buy are just one aspect of this problem—targeted ads can be more than annoying; they can be actively harmful to democracy, our mental health, and our privacy. They’ve been used to target by race with disinformation about elections and used to convert and recruit for churches.

What are data brokers?

Big Tech companies deserve to be held accountable for privacy violations as they are fully culpable and need to do a lot better than they collectively do.

But, some companies operate away from the spotlight, away from regulations, and away from most internet users’ knowledge.

These companies are known as data brokers.

In Europe, there are decent privacy laws that try and work to protect citizens. But in the US, privacy laws are far less restrictive, and data brokers can have up to 1,500 pieces of information on average about each American citizen.

Data brokers (aka “data suppliers,” “information brokers,” “data providers”) either collect our personal data themselves or buy it from other companies, like social media platforms, credit card companies, or any website that passes along or harvests our data. And while most of us aren’t even aware these companies exist, it’s a 200 billion dollar industry and still growing quite rapidly. There are over 4,000 data broker companies.

Data brokers can be anything from credit reporting companies like Equifax, Experian and TransUnion; to creepy people-search websites like PeekYou, Pipl, and Instant CheckMate, to companies you probably haven’t ever heard of, like Acxiom, Cuebiq, CoreLogic, LiveRamp and Epsilon. And what all these companies have in common is that they collect our personal information and resell or share it with other companies.

As a WIRED reporter said, data brokers are “the unchecked middlemen of surveillance capitalism” and a “threat to democracy.”

While most data brokers buy and sell information about us like “Formula1 enthusiast”, “expectant parent,” or “compulsive buyer,” they sometimes stray into allegedly selling lists like: “rape sufferer,” “alcoholic,” and “erectile dysfunction sufferer.”

How do data brokers work?

Mostly, if we’re talking about digital data, we’re talking about it being collected via third-party cookies or scripts. This means that companies other than the site you’re on are setting cookies to collect data about you and watch what you do.

It’s important to note that not all third-party scripts are malicious, nor are all cookies harmful. Fathom, after all, is third-party JavaScript our customers embed on their sites. And most sites with a login form have to use cookies to keep you logged in.

The difference for Fathom here is that we are very public and very strict about our data collection practices and go above and beyond, adhering to major privacy laws. With data brokers, you’d never find a page on their site documenting how they collect data, what they collect, and how that data is then used.

Another critical difference for third-party scripts like fonts or privacy-focused analytics is that third-party code from data brokers not only follows you around the site you’re on but also follows you from site to site across most of the internet.

For example, the New York Times has 10 ad trackers and 17 third-party cookies to profile your internet usage. Adobe’s site has a whopping 21 ad trackers and 34 third-party cookies. Surfshark, a VPN who touting being privacy-focused, has 9 ad trackers and 3 third-party cookies.

You can run your own tests like the above using The Markup’s Blacklight tool (as linked in the three examples above). And they’ve reported in-depth on the high privacy cost of sites selling our data.

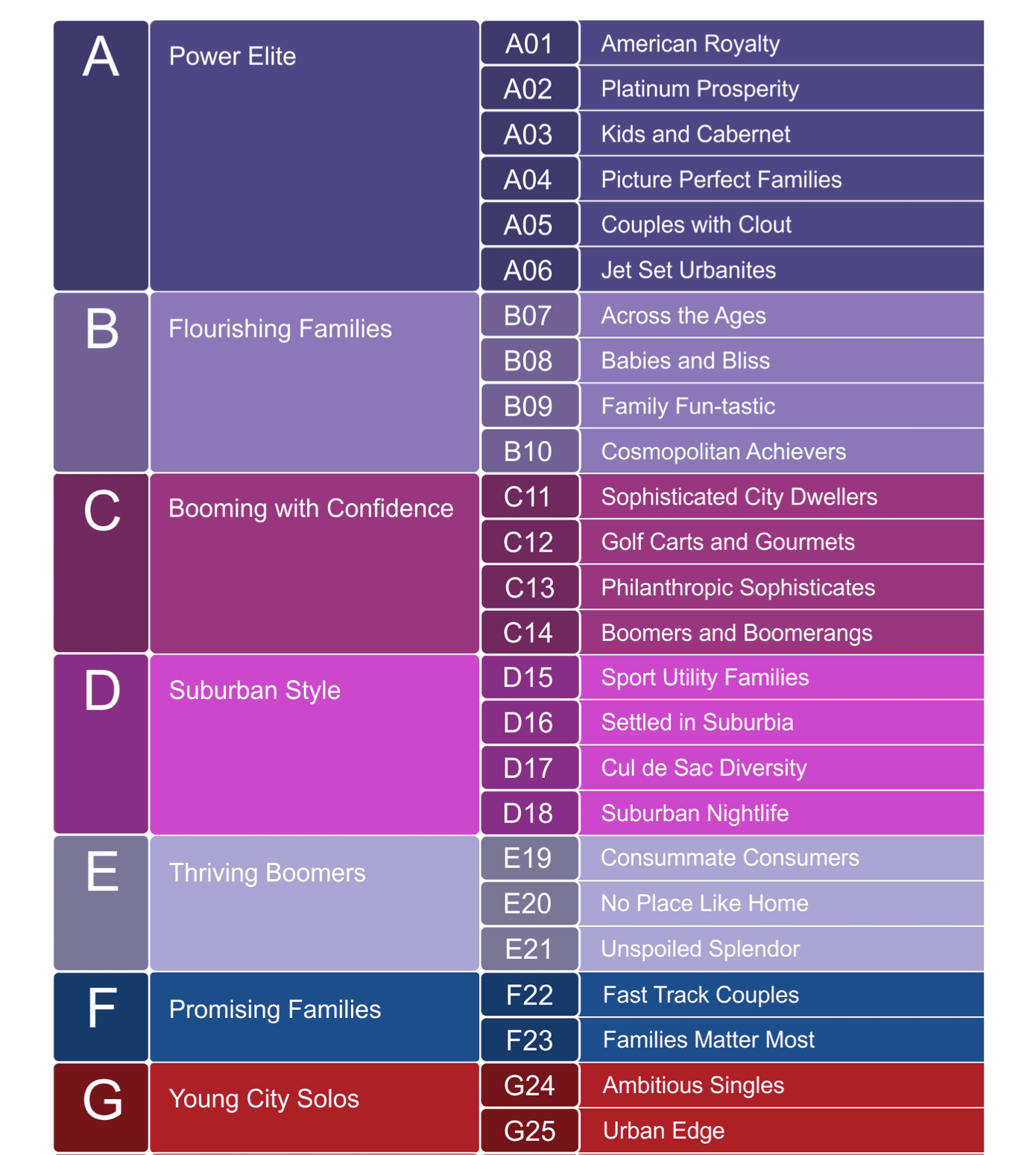

So data brokers collect data points like IP address (which tells you a physical location), device information, and the types of things you’re interested in on the web. Then, they take that data and pair it with other data they’ve collected about you, pool it together with other data they’ve got on you, and then share all of it with businesses who want to market to you. They can eventually build large datasets about you with things like: “browsed gym shorts, vegan, living in Los Angeles, income between $65k-90k, traveler, and single”. Then, they sort you into groups of other people like you, so they can sell those lists of like-people and generate their income.

And while the lists above may seem innocuous to some, some data brokers also sell more invasive lists, like people with specific ailments, sexual preferences, religious and political views, and then sell those lists to anyone. In theory, any person out there could buy a list of data about people with illnesses like cancer, diabetes or even suffer from depression.

If you think medical information with data brokers is protected by HIPAA, you’re unfortunately wrong. HIPAA protects the medical information you relay to your physician (this information is highly protected). But, if you go to a website and search for terms like “abortion” or “cancer treatments” or “find a therapist in Seattle,” that personal information from you is not protected by HIPPA at all.

This doesn’t just happen when browsing websites on your computer, either. Apps on your mobile device can give away data from within the app to third-parties and data brokers too. This can happen without you even knowing it if you use some totally-unrelated-to-location apps like a free flashlight app.

Is what data brokers do illegal?

These companies operate in a relatively gray legal area in countries where it’s legal to collect and sell some personal information. Or, in countries with stricter laws, it can be wholly illegal, but in practice nonetheless.

Most data broker companies work to get around legal issues by burying consent to share data deep in small print and terms and conditions when you sign up or sign into “free” software online or on your phone. They can even be hidden in things like loyalty cards, where you get a small discount, and they get to collect detailed information about you and your purchases.

While most of these data broker companies market that what they do is perfectly legal, they still get in legal trouble, even in countries without strict federal privacy laws like America.

In 2021 Epsilon (one of the data brokers mentioned earlier in this article) was sued by the Department of Justice for $150 million for helping to facilitate elderly fraud schemes. The lawsuit happened after they admitted selling more than 30 million consumers’ data to companies they knew were carrying out scams (and they did this for nearly a decade).

SafeGraph, an ironically named data broker who sells location data, only recently stopped making it possible to buy data showing how many people visited Planned Parenthood locations (as well as where they came from and where they went afterwards). They’ve also been known to sell fully disaggregated data about people to the American government.

Life360 is used by over 35 million people and is touted as a way to keep your family safe by sharing locations with each other. And if you don’t find the premise of their software creepy (keeping precise tabs on family members), they recently got into trouble because a significant source of their revenue (16 million dollars in 2020) was from selling that location data to dozens of data brokers. This includes selling location data of minors/children. The company now insists they no longer do this but had to be exposed to change their practices.

These data broker companies often claim they de-identify the data they collect to remove who specifically the information belongs to. The problem here is that re-identification is relatively easy because the data they collect is so personal and specific.

One study found that 99.98% of Americans could be re-identified using any dataset of at least 15 demographic attributes (like gender, marital status, hobbies, income level, precise physical location, etc.). Per their abstract, “Our results suggest that even heavily sampled “anonymized” datasets are unlikely to satisfy the modern standards for anonymization set forth by GDPR and seriously challenge the technical and legal adequacy of the de-identification release-and-forget model.” On a side note, this is why you won’t find details such as operating system version or browser version in Fathom. The more data collected, the easier it is to single out website visitors, and we refuse to take part in that.

Should I care that data brokers have my data?

You may feel like you have nothing to hide and therefore your don’t care if data brokers collect and sell your data.

You don’t do anything illegal and don’t care who knows what you search for and look at on the internet. And while this can be a risky view, it’s reasonable if you feel that way.

The problem is that not everyone has the luxury or privilege of being able to not care about who follows them around the internet. People may have excellent reasons why they don’t want to be found, don’t want to be spied on, or don’t want their personal data to be bought and sold.

And, if you happen to be a person who needs to not be found, spied on, or have their data bought and sold (stalker victims, or victims of domestic violence, for example), there are no federal laws mandating that these data brokers remove your data upon request. Or worse, there are rarely methods to opt-out of being tracked in the first place.

This whole collection of data about all of us also gives the government in America a legal loophole to get around their fourth amendment (the right to protect against unreasonable searches and seizures).

Typically, a government agency needs a warrant from a judge to force turning over data about you. That judge uses their knowledge of the law and discretion to allow or deny the request, which, if allowed, lets the government spy on you without your consent. But, and here’s the loophole, if it’s not forcing a company to turn over data, if instead, it’s buying that data from a data broker without your consent, then that’s totally legal and doesn’t require a warrant at all. And all of this can happen with you even knowing they bought your data and are using it.

What can be done about data brokers?

To recap: far too many websites have third-party scripts and cookies on their site, which transmit our personal information and habits to data brokers, who then group that information with other data they have collected about us from different sources and pool it together to then sell to advertisers, governments, and whomever else wants to buy it.

Even if data is “anonymized,” the sheer amount of data they have on all of us is far too easy to de-anonymize, as there are far too many data points. There’s almost no oversight from many governments (especially in the US) in this industry. Who we are, where we are, and what we are interested in are all for sale. This data about us isn’t ours to have, know about, edit or even remove.

This situation is obviously not ideal, whether or not you care about your own privacy. Mostly because data brokers and companies who buy and sell from them are making billions of dollars of our data without us seeing even a cent. We should at least have the choice for our privacy to be violated, and if we feel that’s acceptable, be compensated for it.

These shady practices of buying and selling data is precisely why Fathom Analytics exists. Our analytics don’t collect personal information, and we go to great lengths to ensure the tiny bit of data we know about website visitors is hashed and salted using a dynamic (constantly changing) salt key. And even then, we display all data we have in aggregate (i.e. not tied to an individual). We sell software, not data, and the two business models could not be more different. We actively argue for more transparency and regulation in this industry and believe that targeted ads should be illegal.

According to Pew Research Centre, roughly six-in-ten Americans believe it’s impossible to go through daily life without having data collected about them by companies and governments. In Fathom’s survey of 1,500 people, 92% of people feel they have no control over their data being collected and shared online.

Legal or not, data brokers know far more about us than we might like and do significantly more with that data than even the more paranoid of us might think.

The economy of most of the internet right now relies on this business model involving data brokers. This is precisely why so many of the most popular websites (and social networks) are free: they make billions from our data. They don’t need to sell a product to us because we are the product being sold. They then don’t have to charge us since that’d mean less of us would use their websites, and they could generate less money from our data. Everything “free” that we take for granted on the internet is only free because they are profiting from our data.

How can we protect ourselves from data brokers?

We can take more precautions on our own (using privacy-focused browsers, VPNs, not agreeing to terms or cookie consents, etc.). Web browsers like Brave, Firefox, and even DuckDuckGo’s newer browsers work by blocking a lot of third-party baddies from being able to collect data to sell to brokers. There are settings to turn off on your mobile device that allow Apps to track our activity on our phones.

Taking matters into our own hands shouldn’t be solely on us to stop our data from being sold without our consent or knowledge. Our digital privacy and digital lives should be protected by default. There have to be legal ramifications and laws against our data being collected without that consent or knowledge.

In the EU, the GDPR law works to thwart data-brokering by mandating that one of six legal bases for data processing must apply to process a person’s data. And, when that’s not the case, there can be lawsuits, fines and warnings. The problem is that most data brokers operate without our knowledge, so it’s sometimes difficult to even know their practices or what they know about each of us.

Even GDPR isn’t perfect, as now companies who pretend to follow that law by showing consent banners make it difficult and time-consuming to opt-out of cookies fully. Most people don’t have time to click through a bunch of screens and toggles and hit “Accept” or “OK” (meaning they are consenting to their data being collected. Which is brilliant, in an evil genius way (queue Hank Scorpio gifs)).

If you are a website owner or in charge of a website, what you can do is clear: make your website a black hole to Big Tech and ensure there are no third-party scripts that send data off to brokers. Remember, not all third-party scripts are evil, but make sure you fully understand how the data is used for each third-party script your site includes. This is why we publish a comprehensive data journey on this website, to let folks know exactly what we collect, exactly how we use it, and how genuinely anonymous we make things.

The practice of buying, selling and sharing our personal data is a sprawling, unregulated ecosystem that operates in the shadows. So, the more of us who know and understand how creepy their practices are, the more we can do things like asking for better federal regulations from each of our governments (as well as not using “free” software that enables data-brokers access to data in the first place).

Note: Some examples in this article are from the Last Week Tonight: with John Oliver episode on data brokers (it’s a brilliant episode). Their research team at the show did so much amazing work, and are even pressuring congress to pass better privacy laws in the US in the most hilarious way.

You might also enjoy reading:

BIO

Paul Jarvis, author + designer

Recent blog posts

Tired of how time consuming and complex Google Analytics can be? Try Fathom Analytics: